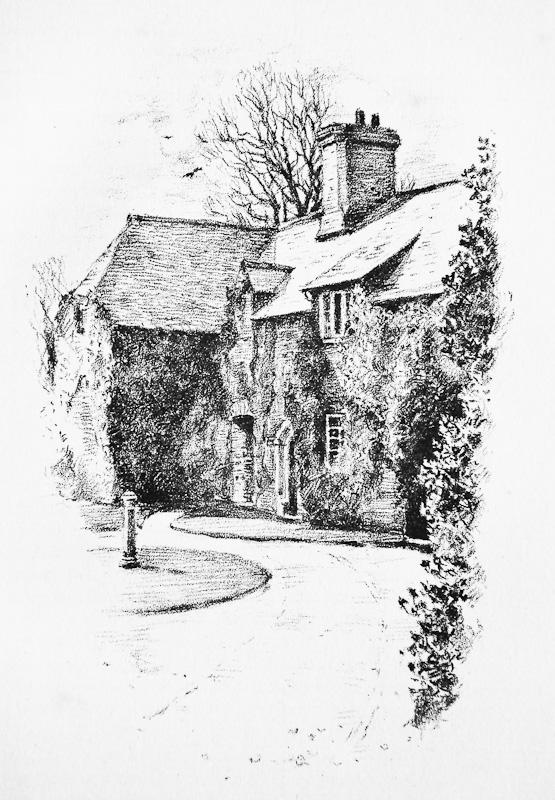

Old Whitstone House

* * * * *

No portrait exists of Hawker’s first wife, Charlotte. Writing to a friend after her death, Hawker expressed his regret that she could never be persuaded to sit for a photograph ‘because I should have liked that others might have known the features that I can never forget’.

‘Her face was indeed a perfect image of noble Womanhood – oval – blue-eyed – with a nose slightly curved somewhat like my own – a firm mouth, and a forehead moderately high banded with soft light hair that never turned gray to the last. But it was the expression that was so striking. You could see every kind emotion and loving impulse on her face and She never heard a good thought or noble sentiment without moistened eyes and quivering lip. In my dining room there hang upon the wall pictures of her two elder Sisters, Twins, her youngest Sister and her Father. She was most like the latter – but of her dear face no outline except that graven on my heart and that comes to me ever and anon in dreams.’

(Life and Letters, p. 484)

According to Hawker, Charlotte was well able to justify her objections to photography, or ‘sun-pictures’: ‘She used to say that every person who had a Photograph taken tried to call up a forced and unnatural expression under the notion of trying to look better and otherwise than their natural countenance and therefore the result was failure’. Plenty of people still feel this way, despite advances in photography, but the pictures of her father and sisters which ‘hang upon the wall’ are presumably paintings rather than photos, and her reluctance seems to have been based on an innate dislike of the whole business of portraiture. To resist the pressure of loved ones over an entire lifetime must have taken a good deal of determination – Hawker himself underwent a number of photographic sessions, and his wish to possess her image seems likely to have been expressed in fairly robust terms.

A few other descriptions of Charlotte have survived to be passed down to us. C. E. Byles in The Life and Letters includes the account of ‘The late Mr. Christopher Harris, at whose house, in 1827, Hawker wrote his “Inscription for the Waterfall at Hayne,”‘. Not long after Hawker’s death Mr Harris shared his recollections of Miss I’ans with the readers of ‘John Bull’:

“We saw the lady,” he says, “in 1816, then at the age of thirty-three, eight years before her marriage. She was tall, fair, and comely, with suave and winning manners, and very accomplished. Her elder sister, Florence, shone in conversation, and was yet more good-looking. In the society of these ladies, at Bude, Hawker spent most of his time. Young, handsome, and brilliant, he was ever a welcome guest. His craving after knowledge was notorious. Books such as he desired were not to be found at Stratton; and the library at Whitstone, small yet well selected, furnished the means of gratification. A similarity of tastes was the bond of union between the attractive preceptress and the diligent pupil; they paid the usual penalty of propinquity, and their relative positions became quickly reversed . . . . . This did not escape the vigilant eye of the second and elder sister; but the caution that was honestly given came too late for preventive purposes . . . . . It was in vain that a fearful disparity of years was urged, which, in the course of time, might have unfortunate results, and bring sorrow to both. The advice was most sage and judicious, and, as is usual in such case, when the maggot bites, was utterly disregarded.”

” In this instance it should be observed,” continues Mr. Harris, ” and we do so with singular pleasure, that the auguries of the elder sister failed of consummation, and to no one did it cause greater satisfaction than to that lady herself. We knew the Vicar of Morwenstow and his first wife during the whole time of their married life, and to the very last their mutual affection remained unimpaired in the sanctity of their plighted troth.” . . .

(Life and Letters, p. 16)

Margaret Dyne Jeune, describing a visit paid by herself and her husband, Francis Jeune, to Morwenstow vicarage in 1847 (Pages from the Diary of an Oxford Lady 1843-1862, p. 9) comments that: ‘We had enjoyed ourselves much and could not but be gratified by the hearty welcome given us by this old friend of my husband and his wife – a lady many years older than himself and with a sadly strong Cornish accent, but a woman of good commonsense, well-read and informed; in her youth she must have boasted of no small share of beauty.’

Efford Manor (now Ebbingford Manor), Bude

* * * * *

The baptism of Charlotte Eliza Rawleigh I’ans was recorded in the register for the parish of Whitstone, Cornwall, on 6 December 1782. Very few of Charlotte’s papers survive, but Lois Ijams Hartman, a distant American relative, has recorded some information about the I’ans family in a privately published booklet, Remembered in This Land. Charlotte was one of seven children of Colonel Wrey I’ans and Frances Rawleigh. The dates of birth of her brothers, John, Edward, and Thomas, are unknown, but her older twin sisters, Florence and Frances, were born in 1776 and her younger sister Catherine in 1785. Charlotte’s ancestors, like Hawker’s, originally came from Devon and her great-grandfather, Thomas I’Ans, worked at one time as a ‘customs collector’ in Bideford.

Thomas I’ans probably purchased Old Whitstone House in the early eighteenth century. During Charlotte’s childhood Colonel Wrey I’ans also took on the lease of Efford (now Ebbingford) Manor in Bude. Efford is generally supposed to have been the scene of Hawker’s proposal to Charlotte but the family appear to have divided their time between the two houses. Hawker and Charlotte stayed at Whitstone during his vacations from Oxford and he studied there in a hut in the woods when he was preparing for Deacon’s orders after his graduation.

Charlotte was forty-one and Hawker only nineteen when they married. Although some accounts describe her as his godmother this was not the case – they did not meet until after his father moved to Altarnun when Hawker was about eight years old. The newly married couple lived together in Oxford while Hawker continued his studies and were joined for part of the time by two of Charlotte’s sisters. After Hawker’s installation as vicar of Morwenstow, Charlotte supported him both practically and financially in running the parish and caring for the poor and needy. Despite the differences in their ages and backgrounds the impression given by Hawker’s letters, and confirmed by the accounts of those who knew them, is of two people of similar outlook, well-matched in their dedication to a common goal.

Charlotte’s health and eyesight deteriorated as she grew older, and Hawker cared for her devotedly at considerable cost to his own physical and mental well-being. His description in a letter of 1856, of reading aloud to her in the afternoons while she ‘works or knits’, provides a touching contrast to the reports of bad weather, parish disputes and financial worries which fill much of his published correspondence. Charlotte was the only one of the seven I’ans siblings to marry, and outlived all of her family. She and Hawker had no children and his outpourings of grief following her death in February 1863 make sad reading.

She is buried in Morwenstow church, ‘just outside her Seat door in Church where the Chancel meets the Nave’, and her stone bears the inscription:

There is sprung up a light for the righteous: and a joyful gladness for such as are true-hearted.

A memorial to Charlotte Hawker in Morwenstow churchyard.

All illustrations by J. L. Pethybridge from The Life & Letters of R. S. Hawker by C. E. Byles.

* * * * *

ADDENDUM – 26 MAY 2012: While writing this piece I was aware that information was lacking as regards Charlotte’s schooling, however a snippet from the Preface to C. E. Byles’ The Life & Letters has since caught my eye. Expressing his thanks to the publisher, John Lane, Byles mentions in passing that Mr Lane’s grandmother, Mary Isabella Hobbs of Whalesborough, near Bude, had been a schoolfellow of Charlotte’s, and that this ‘gave Mr Lane an early interest in the Vicar of Morwenstow’. If anybody reading this knows which school Mary Isabella Hobbs attended I’d be grateful to hear from them via the website contact form.

Text © Angela Williams 2012

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Follow Me, or Lost and Found: A Morality from the German. C. E. H., Morwenstow. James Burns, London. 1844.

‘Earl Sinclair.’ Translated by Mrs Hawker from the German of Oehlenschlager. Sharpe’s London Magazine, 6 Dec, 1845.

‘Too Late’, a translation from Toni, appeared in Household Words, Volume 8, No. 202, 4 February 1854. The Dickens Journals Online website describes it as a piece of short fiction by Charlotte Elizabeth [sic] Hawker on the following subjects: Crime; Criminals; Punishment; Capital Punishment; Prisons; Penal Transportation; Penal Colonies. Russia—Description and Travel. Russia—Politics and Government. Unfortunately it isn’t available to read as yet.

Two poems, ‘The Wreck’ and ‘Earl Sinclair’ are both included in Cornish Ballads and Other Poems by R. S. Hawker, edited by C. E. Byles. John Lane, 1904.

RECOMMENDED READING

Remembered in This Land by Lois I. Hartman. Privately printed. Stapled booklet, 78pp. No date but probably circa late 1970s.

The Vicar’s Wife by Lois I. Hartman. Minerva Press, 2000. Read more here . . .

Footprints Beside Him: a poignant love story of the Cornish Coast. Hillcrest, 1984. (An earlier version of The Vicar’s Wife.)

FURTHER LINKS

– Online Parish Clerks, Whitstone, Baptisms: Charlotte Eliza IANS

Comments

One response to “Charlotte Eliza Hawker (1782-1863)”

I do not know the answer to your question about Charlotte’s schooling but would be very interested in a biography of his second wife, Pauline.